- Home

- Kelly McClorey

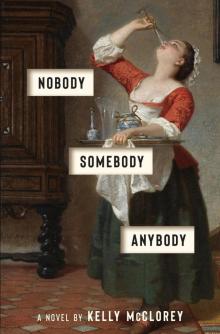

Nobody, Somebody, Anybody

Nobody, Somebody, Anybody Read online

Dedication

For my parents

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

One

On my first day as a chambermaid, two guests were in the hallway discussing the Commodore’s Ball, and I heard one say to the other, “Why don’t you ask that lady?” It took a moment for me to realize “that lady” was me, stooped over a trash can to replace the liner, but when I did, I felt proud and didn’t mind that they had no idea who I was or that I had in fact attended college, a rather elite university. They never did ask me a question, but I quickly forgot about that, as I was too busy thinking Lady with the Trash! I’m the Lady with the Trash! because that sounded like Lady with the Lamp, nickname of none other than Florence Nightingale, hero of medicine and hero of mine, who stayed up all night ferrying her lamp from soldier to soldier, providing lifesaving care to the sick and wounded. Someday I hope to be known for that level of devotion.

As I finished with the trash, Roula appeared and told me to take my first break. I meandered down from the hotel floor into the dining floor, with the kitchen, offices, and trophy room, then into the harbor floor, with the lounge, ballroom, and deck, staked up on poles over the ocean. From the deck I had a brilliant view of the members’ boats lolling about, all pristine and lovingly named, most with masts waiting to be draped in magnificent sails, as pure white as the sheets and towels I’d folded that morning. I settled with my arms dangling over the railing to watch as boys in polo shirts bustled about the T-shaped dock. One of them drove the launch boat that picked members up and towed them out to their own, bigger boats.

An elderly woman plodded down the dock, escorted by a man and a teenage boy. The man and boy had blond hair curling out of their heads and their calves, which were muscular and bronzed. She wore a whole rigging of jewelry so that I could hear it jingle from all the way up there and see it sing in the sunlight, flashing off her knuckles and wrists and the side of her head, where she must have pinned a fancy barrette. I was watching her slow, glittery progress when Doug, the general manager, sidled up beside me. “You don’t want to be rich,” he said, pressing the solid bulk of his belly against the railing. The skin on his forearms burned with a deep rusty tan. “I knew this one guy. Had the most massive house I’ve ever seen—you’d want to call it a castle really. But he was so lonely up there, he went nuts. One night it got so bad, he spooned three thousand dollars’ worth of caviar into a bowl of water. In hopes it would hatch!”

He gave me a serious, purposeful look. Apparently he thought I was dumb enough to believe there was a direct correlation between wealth and loneliness and, on top of it, that correlation implies causation, as though I’d had no higher education. Plus, didn’t a place like this—an exclusive private yacht club created by wealthy people for the purpose of socializing with other wealthy people—offer evidence to the contrary? Still, I didn’t intend to make sweeping generalizations. Florence Nightingale herself had grown up with two beautiful homes! One in Derbyshire, one in Hampshire.

“I was only thinking about sea squirts,” I said. “They live under docks and boats.” To convince him, I kept going. “Have you seen them around here? They can look kind of like fingers or flowers, or little tubes of jelly.”

“Oh sure. We’ve got to scrape them off every few months,” he said. “They can damage the equipment.”

“Maybe. But did you know they also have compounds shown to be effective in treating certain kinds of cancer? I guess you never know about those things, what might be hiding just under the surface.”

“I hadn’t heard that.” He fingered the perspiration on his forehead. “You are a fount of knowledge.” He grabbed the face of his watch and grunted.

As he walked off, I noticed that the old woman and her two companions had made it into the launch boat. I watched the boat move away slowly, water opening and closing behind it like a curtain. Then Doug reappeared at my side, startling me. “One other thing, Amy,” he said. “I’d prefer if you didn’t take your breaks out here. The deck’s for members only.”

That evening, while the members enjoyed the Commodore’s Ball—a special centennial edition to celebrate the club’s one hundredth season, according to a flyer on the events board—I opened Florence Nightingale’s biography. I reread all my favorite passages, dizzy with inspiration. She emphasized the vital importance of cleanliness: it was poor sanitation, not battle wounds, that had caused the vast majority of fatalities in the Crimean War, and she used data analysis to prove it, then illustrated her findings in an elegant coxcomb chart that made it easy for Queen Victoria to understand. She also wrote advice for ordinary people. Dirty walls and carpets can be as unhealthy as a dung heap, and tidying can’t be done by simply flapping dust from one surface to another; dust should be removed completely with a damp cloth. All this reinvigorated me for my second day on the job, as did her many remarkable quotes. For instance: “I attribute my success to this—I never gave or took any excuse.” I copied that down, as they were words to live by.

* * *

Four weeks have passed since then, four weeks that I’ve been working as a chambermaid, which isn’t technically my title, but I prefer it to housekeeper because of the rich history associated with the word maid. For instance, it was milkmaids who helped discover the smallpox vaccine. They noticed that those of them who had contracted cowpox from tugging on infected udders were later immune to smallpox, and their observation prompted Edward Jenner to extract pus from a heroic milkmaid’s arm and inject it into an eight-year-old boy. History remembers them all, even the maid.

Although this is only a summer job, I strive never to treat it as such. I strive to treat each guest like family, or better than family, because isn’t it true that we tend to treat our own family worse than enemies, believing we can get away with anything, and they’ll never leave us? And since I’m about to become an EMT, once I pass the exam on August 25, I approach this job and everything else in my life with the knowledge and sense of responsibility of any reputable medical professional. The voice of Hippocrates, the world’s first epidemiologist, came to me once as I flushed scum down a sink: “Is the water from a marshy soft-ground source, or is the water from the rocky heights? Is the water brackish and harsh?” He recognized water as one of the most important environmental factors when it comes to the spreading of disease, and right alongside water is cleanliness, which is why a job like this should only be undertaken with the utmost care. I’ve never been a germophobe—I can appreciate the value of exposure for building a strong immune system—but here I’ve become haunted by an open toilet lid (particles can travel up to six feet during a flush!) and, what’s worse, a toothbrush sitting unprotected within that six-foot radius. I dunk unprotected toothbrushes in hydrogen peroxide, performing a sort of covert baptism. I’m extra cautious ever since Roula barged in and yanked the toothbrush out of my hand as though I were a child. “What are you doing, touching that?” she sneered. When I tried to explain, she cut me off, saying, “Just stick to the checklist.” To her, a checklist is like God’s final word.

The guests here are wealthy and tan and have a love of boating, and in order to stay in one of our rooms, they must be members in good standing or else have gone through the proper channels to be “introduced,” whic

h requires a member in good standing to accompany them to the clubhouse or write a letter or make a phone call on their behalf (but if there is only a letter or a phone call, they must wait at least fourteen days before being introduced again). We have only ten rooms on the hotel floor, though the workload varies depending on the number of stay-overs versus checkouts, with checkouts taking nearly twice as long. I always start by coating the shower and toilet with chemicals, allowing them time to penetrate while I refresh the dish of potpourri and swab the light bulb, a trick to instantly brighten any room. Once I have the porcelain and chrome glistening, the fumes stinging my eyes, I prepare to move into the bedroom by discarding my gloves and steeping my sponges in detergent. When it comes to making the bed, Roula taught me “The queen is always right,” as a way to remember that tags on king sheets are on the left, while tags on queen sheets are on the right. Tags should always, always face down.

Roula and I share the housekeeping closet, where we store our cleaning caddies and hang our personal belongings on side-by-side hooks. There’s a small table for our paperwork and a telephone, though she also keeps three potted plants there, to mark it as her domain. Although she holds the title of head housekeeper, she puts far more effort into caring for these plants than she does for any of our rooms, as far as I can tell. She dotes on them throughout the day, adjusting their positions as the sun moves across the window, spritzing and trimming their leaves, testing the soil with her finger. It can get isolated up here with just the two of us, so for a while I tried spending my breaks in the alley where the waitstaff hang out, smoking and using their cell phones and sipping on iced coffees they fill up for free in the kitchen. They’re young except for one guy they call Shell, from his last name, Shelling. He must be at least two decades older than the rest; you can see it around his eyes, even though he’s kept lean and has a full head of wavy brown hair. He works another job in the evenings, at a restaurant in Boston where the employees are paid to be rude to the customers—they write personalized insults on paper hats and place them on your head during the meal, and if you ask for a napkin, they throw it at you—but he’s an actor first, I’ve heard him say that a few times. All because he once had a tiny role in a Bill Murray movie, a single line, something about the bricks being fake.

The last time I went to the alley, the lunch rush had just ended, and two girls I’d seen out there before, Liza and Bridget, were resting against the wall of the clubhouse. When I said hello, they nodded. Liza held a cup of ice and was munching on the cubes one at a time. Bridget kept fishing around in her purse, a repurposed rice bag sewed with leather straps. Shell sat on a crate and puffed smoke. Two other servers lobbed a tennis ball back and forth, occasionally doing tricks with it, slinging it from between their knees or behind their backs. One of them, Vinny, wore a Red Sox cap. I hadn’t learned the other’s name, though I recognized him by his uneven gait—he was pigeon-toed.

“You’re a senior, right?” Shell asked as he scooched the crate closer to Liza.

She gradually tongued an ice cube to the side of her mouth, annoyed by this inconvenience. “Going to be,” she mumbled, her cheek bulging.

So she must be just a few years younger than I am, I thought, arranging myself against the wall beside the girls. Bridget spun the two bracelets on her wrist. I watched the rotations until I could make out the words engraved on them: WANDERLUST, SIMPLICITY.

“Aw. And I’m just a measly sophomore,” Shell said. He turtled his head, trying to look shy.

“Ha, ha,” Vinny said as he snatched the tennis ball from the air with one hand. “I thought you had to stay a thousand feet from any school.”

Shell grinned. “Now, that’s not very nice.”

“What college?” I asked Liza.

“No,” she said, “high school.”

Bridget’s phone dinged in her palm. She leaned toward Liza and said in a low voice, “M is asking about the bonfire. What do you want me to say?”

“Did you say bonfire?” Shell said. “Now, that sounds like fun.” He looked at me. “How about you, do you like bonfires?”

“I guess.”

“What a coincidence! So do I. So, ladies, what time should we be there? Come on, now, it’s not polite to whisper.”

“Everyone’s going to be in high school.” Bridget typed on her phone without looking up. “I really hope you have better things to do.”

“I don’t! And what about poor . . . what was your name again?”

I hesitated, but saw no other option. “Amy.”

“Right. And what about poor Amy? You’re just going to exclude her too?”

“Leave her alone,” the pigeon-toed waiter said, taking a step toward us.

I cast him a look, then turned back to Shell and the girls. “Yeah,” I said. “Are you just going to exclude us?” I put my hand on my hip.

“Ha!” Shell was getting excited. “You tell her, Amy.”

Liza spit her ice cube onto the pavement and said, “Jesus Christ. If you guys really care that much, you can come. This is depressing.”

“Now, that’s more like it,” Shell said, and turned to me. “What time shall I pick you up?”

“I was just trying to do you a favor,” I said. “Personally, I have better things to do.”

“Oowee!” Vinny celebrated, raising his cap to the sky.

The girls clucked, and I tried to laugh lightly along with them, but I was feverish from the whole exchange, feeling bold and almost deranged, so that when Vinny pitched the tennis ball to his pigeon-toed friend, I sprang forward with my arms up, making a pocket with my hands, and heard my voice call out, “It’s mine!” The ball landed inside. It was hot and woolly. They looked at me and I looked at them; we were all waiting. I wasn’t sure what to do or why I’d caught it in the first place.

I faced the girls, the ball raised in my hand. “Let’s all play,” I said.

They gaped at me. The ball bore into my palm. I thought I could feel blisters forming.

“How about monkey in the middle,” Shell whispered, just loud enough for everyone to hear.

I turned and chucked the ball blindly over my head toward the pigeon-toed one. It had too much force and bounced behind him, down toward the dumpsters. We all stood watching it. Shell laughed a little. Finally, the pigeon-toed boy said, “I’ll get it!” but I didn’t wait around for that.

* * *

Over the last four weeks, I’ve come to enjoy many aspects of the job, particularly the experience of scouring. Friction is a spectacular force. I am an extension of my sponge, absorbing the dirt and dust and grime and feeling them dissolve into me so that we, the dirt and I, become one. Together we sail from room to room, always moving top to bottom and clockwise to prevent the corruption of previously cleaned areas. Naturally, I’m curious about the items that belong to such wealthy, tan, boat-loving people, particularly the cosmetics. Each woman has curated her own collection to highlight her assets and cover her problem areas, and while I don’t normally buy cosmetics myself, I appreciate this exposure to the cutting edge of high-end beauty. Just today, I stumbled upon a pot of 24-karat gold butter that, according to the label, should be applied with a vegetable sponge for luxurious exfoliation. I cupped the pot in my hand and squinted at the sparkly stuff inside, even twisted off the cap and took a whiff, but I would never go so far as to dip a finger.

The attention required to root out grime can be taxing, though, and I feel constant pressure to outdo the previous day’s job in order to enjoy a sense of accomplishment and to please Roula, who has worked here ever since immigrating from Greece and so has the benefit of experience, even if she lacks initiative and shrugs it off when I bring up important issues like the invisible breeding ground on light switches and doorknobs. My small frame can be both a help and a hindrance: I must be a gymnast when I reach behind the sink, a weightlifter when I wrestle up a mattress. My back throbs from all the crouching, and when I creak up from my mashed-in knees, I often murmur with pain, and thes

e murmurs sound honorable to my ears, and so urge me on. Imagine, I sometimes say to myself, the pain Roula must feel, given that she must be fifty years old or close to it, while I am lucky to be so young—not yet thirty and not yet tied down.

For a college course, I once read about a study in which researchers found that when hotel maids started to view their work as a form of exercise, they lost weight and became more physically fit, even though they were performing the exact same activities as before. That got me marveling at the power of belief: you never know what’s possible when the mind and body agree to work together. Our guests probably spend a fortune on gym memberships and personal trainers, and here I am, the chambermaid, collecting their filth and dissolving it into myself and meanwhile burning enough calories to lose two pounds in four weeks simply by believing in my own movement. Whenever I scrub the grout between tiles, I feel the hump of my bicep growing more defined.

Each room has a wooden hutch that opens to reveal a widescreen television, and I often turn it on while I clean, since it doesn’t distract me but rather sinks me deeper into the rhythms of my work. My only rule is no changing the channel—that way I’m connected to the guest and don’t waste time searching for another program. It’s usually Oprah or twenty-four-hour news or a soap opera or one of those shows in which everyday people sign up to get into an argument or receive relationship advice. Before long, the voices from the television seep into my brain, and not just my brain but my arms and legs, which begin to move with a different attitude and style, as though connected to someone new. Like this morning, while Eva pledged to make Jad pay for the death of her daughter, I plumped pillows and shook crumbs from a summer quilt with all the righteous anger of a vengeful mother. Sometimes I notice my voice following along, adding a snippet of commentary here and there, though if I hear any footsteps in the hall, I trail off and pretend to be humming a tune. Roula likes to remind me that I’m not allowed to turn on the television, it’s unprofessional, but I know that if she could see the way I am there but not there, cleaning but not cleaning, exercising but not exercising, she would not only understand but emulate my routine. She probably wonders how on earth I’ve ended up here, seeing as I did go to college, which has a lasting impact on everything I do, even if I didn’t graduate. I’ll admit that sometimes I wonder the same thing, but then it’s just for the summer, so there’s no use dwelling on it.

Nobody, Somebody, Anybody

Nobody, Somebody, Anybody